Urban heat island are urbanized areas exposed to higher temperatures than the outer regions. Structures such as buildings, roads, and other infrastructure absorb and re-radiate more of the sun’s heat than natural landscapes such as forests and bodies of water. Urban areas, where these structures are very dense, and greenery is limited, become “islands” with higher temperatures than outside areas (URL 1).

Urban heat islands are more common in metropolitan cities where the population is dense. Many elements such as human activities, transportation, industrial, and building stock form urban heat islands. We burn energy in many activities in our daily life, and the point that people burn usually escapes in the form of heat (URL 2). And if many people are in an area, that means a lot of heat. The difference is especially noticeable at night when the heat captured by pavements and buildings during the day continues to warm the city after the sun goes down (URL 3).

Large cities can be up to 12 °C warmer than their surrounding environments in the evening (URL 3).

Many factors, from how cities are built to building materials, affect the effect of the heat island. Green areas do not support places with intense construction and are the areas where the heat island effect is seen the most. Cities are already exposed to higher surface temperatures due to the urban heat island effect, which can also affect the regional climate (URL 4).

Heat islands increase the demand for air conditioners to cool buildings. The highest need usually occurs on hot summer weekday afternoons when offices and homes run air conditioning systems, lights, and appliances. Electricity supply companies typically rely on fossil fuel power plants to meet most of this demand, increasing air pollutants and greenhouse gas emissions.

Heat islands contribute to higher daytime temperatures, reduced nighttime cooling, and higher levels of air pollution. These pollutants harm human health and generate ground-level ozone (smoke), delicate particulate matter, and acid rain. These, in turn, contribute to heat-related deaths and illnesses such as general malaise, breathing difficulties, cramps, exhaustion, and non-fatal heatstroke (URL 1).

Vulnerable populations are particularly at risk during these events. Children’s faster breathing rates, relative to their body size, time spent outdoors, and developing respiratory systems, increase their risk of severe asthma and other lung diseases, often caused by increased ozone air pollution and smog during heat waves. The elderly are as vulnerable as children. Employees who spend most of the day outside and whose working environment is out are at higher risk of catching diseases due to high temperatures. The low-income population, where urbanization is intense and irregular and environmental conditions are not good, is among the groups with this effect (URL 1, 4).

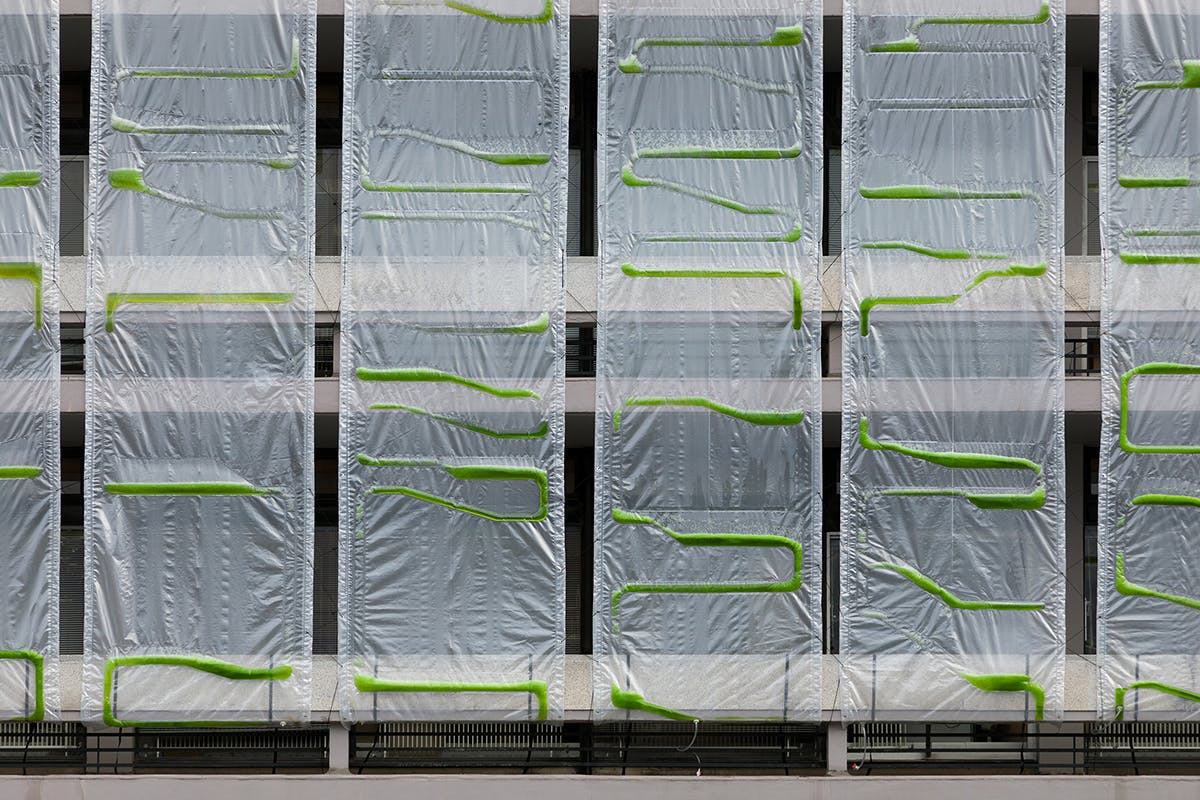

Urban areas need better development planning and a balance of social, ecological, and economic factors. The proper ratio of built and open spaces is essential for enhancing the urban heat island effect. One of the steps to be taken for this is to improve the thermal environment around buildings by using materials with lower absorbency, more excellent thermal conductivity, and higher reflectivity (URL 6). Many activities such as cool roofs, green roofs, and cool coverings and increasing tree and vegetation cover, road widths, and landscape design will help reduce the heat pressure in the city (URL 7).

The priority is to measure the heat island effect to reduce the urban island effect. Establishing planning strategies by evaluating this measurement is the most accurate method to minimize the impact. A policy of reducing the effects on the modeling of heat islands and continuous monitoring of these heat islands should be established by making heat measurements. The practice of green and sustainable urbanization integrates monitoring and planning, improves air and water quality, reduces the heat island effect, cools cities, and protects biodiversity and threatened species.

References

URL 1: EPA, Heat Islands Impact.

URL 2: National Geographic, Urban Heat Island.

URL 3: Climate Atlas of Canada, Urban Heat Island Effect.

URL 4: U.S. Global Change Research Program, Fourth National Climate Assessment Chapter 11: Built Environment, Urban Systems, and Cities.

URL 5: World Meteorological Organization (WMO), Urban Heat Island.

URL 6: Cidco Smartcity, Urban Heat Island Effect — Causes and Remedies.

URL 7: EPA, Heat Island Cooling Strategies.

URL 8: Berkay Kalaycık, Çağrı Mert Bakırcı, What is an Urban Heat Island? How is it formed? How Can We Prevent?